- Home

- Philippe Girard

Toussaint Louverture Page 24

Toussaint Louverture Read online

Page 24

A few years earlier, Louverture probably would have backed down in the face of such determined opposition. But he increasingly saw himself as an autonomous leader rather than a general subject to military discipline. He was also concerned by reports that France would soon launch an expedition to oust him from power, and that it would first make landfall in Santo Domingo.

The situation in France had indeed changed dramatically. In November 1799, Napoléon had seized power and made himself first consul. The Directory that had ruled France since 1795 came to an end; the era of the Consulate began. Napoléon ordered a general review of French colonial policy. His views remained tentative at first, but after hearing of Louverture’s treasonous diplomacy with Britain, he assembled an expeditionary force in the port of Brest. Because of various practical hurdles and Louverture’s victory in the War of the South, Napoléon eventually chose to send the fleet to Egypt instead of Saint-Domingue; but to confuse the British, he ordered Louverture’s son Placide out of his school and onto the fleet. Louverture’s spies in France informed him that Placide was on his way to Brest: “It seems self-evident,” they said, “that the expedition is destined for the Spanish part of Santo Domingo.”7

Louverture chose to invade Santo Domingo at once before Napoléon could strike. To avoid an open break with France, he did not publicly reveal his rationale, instead emphasizing the problems stemming from Santo Domingo’s sanction of slavery. Spanish slave traders, he claimed, were routinely crossing the border with Saint-Domingue to capture black laborers and sell them as slaves in Santo Domingo. Only by putting all of Hispaniola under his control would it be possible to safeguard his countrymen’s freedom. It was a story designed to resonate with his black followers and French progressives.8

Early in January 1801, two army columns began their march. The first, under Moïse, left Cap and headed for the city of Santiago in northern Santo Domingo. The second, under Louverture’s brother Paul, left Port-Républicain and headed for the colonial capital, also known as Santo Domingo, on the southern coast. Louverture did not normally supervise military campaigns in person, but this time he left with his brother’s column. The French envoy carrying official orders not to proceed with the takeover was expected to arrive in Cap at any time, and he did not want to be there when he did.9

Spanish authorities in the city of Santo Domingo learned of the invasion as they were gathering to celebrate the Feast of the Epiphany. They were stunned. Terrified that the horrors they associated with the Haitian Revolution would soon be repeated in their colony, they hurriedly prepared to defend themselves, but their forces were hopelessly outmatched. Paul Louverture’s southern column promptly brushed aside 1,500 Spanish troops at the Nizao River, after which the road to the capital lay open. Just two weeks after Louverture’s army set out, it made camp outside the gates of Santo Domingo. So swiftly had his infantrymen traversed Hispaniola’s mountainous terrain, he noted gleefully, that they had been forced to pause to give the cavalry time to catch up.

After the Spanish agreed to a cease-fire, Louverture triumphantly entered Santo Domingo, the oldest European city in the Americas. Louverture had once served as a black auxiliary of the Spanish Army. He cheekily reminded Governor García that, had the Spanish crown treated him better in 1794, he “would still be in its service.” Local inhabitants hovered between shock and panic. To be governed by a black general and ex-slave was unthinkable for elite Dominicans, whose society was structured along racial lines. Always the first to confront racial prejudices head-on, Moïse organized balls in which the proud Spanish nobles were expected to dance with their black slaves. Spanish colonists prepared to depart for Venezuela and Cuba en masse.10

Most historians take it for granted that Louverture formally abolished slavery in Santo Domingo, but contemporary sources are remarkably unclear on the matter. No emancipation decree has been found; none was included in a detailed account of the invasion printed on Louverture’s orders. To prevent an exodus of colonists and their slaves—that is, taxpayers and workers—he tried to convince the Spanish planter class that he was no radical, even as he wished to be celebrated as a liberator by their slaves. His proclamations were contradictory. “The Republic does not want your assets, only your hearts,” he reassured Spanish planters before the invasion. Then, after the invasion, he told Dominican slaves that they would enjoy their “liberty” and receive a fourth of the crop as salary, just like the cultivators of Saint-Domingue. But he immediately insisted “that they work, even more than before; that they remain obedient; and that they do their duty with diligence, being fully determined to punish severely those who do not.”11

Freeing the slaves of Santo Domingo should have been a landmark moment in the history of the Caribbean, but Louverture’s version of wage labor was so strict that the difference between it and slavery was lost on many contemporaries. “General Toussaint Louverture did not proclaim the liberty of their slaves during the takeover,” Spanish planters remembered many years later. Even legal experts were confounded: manumission documents issued in Santo Domingo in 1801 hint at a chaotic situation in which layers of Spanish and French law overlapped while slavery effectively remained in place.12

Louverture’s refusal to radically transform Santo Domingo’s society left a gaping hole in his political legacy. He had been absent for the abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue in 1793, when he was in the Spanish Army; his equivocation in 1801 meant that his name would not be associated with the abolition of slavery in Santo Domingo either. Dominican slaves were only fully freed during a later Haitian invasion in 1822, and it was in honor of “Papá Boyé,” Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer, that the slaves sang.13

Louverture’s actions did serve his short-term goal: it averted a mass exodus. Out of a total population of 125,000, only 10,000 people left for other Spanish colonies (among the emigrants were the remains of Christopher Columbus, which were taken to Cuba and later Spain). With his customary vigor, Louverture proceeded to develop a colony that was twice the geographic size of Saint-Domingue but had never matched its agricultural output. In an effort to foster large-scale plantation agriculture, he improved roads, lowered export taxes, and banned sales of small plots of land.14

Leaving his brother Paul in charge, Louverture headed back to Port-Républicain. Sitting on a throne draped with silk, he attended an elaborate ceremony in his honor. Golden letters placed above his head proclaimed to the world, “God gave him to us, God will preserve him for us.” He then proceeded to the next item on his agenda: annihilating the last remnants of political opposition.15

One of Louverture’s foremost goals during his political ascent was to arrogate to himself the powers traditionally ascribed to France and its representatives. He proceeded cautiously at first: he had encouraged Laveaux and Sonthonax to leave the colony to become deputies in the French legislature. But Louverture became bolder with time. To force Hédouville to embark in 1798, he asked his nephew Moïse to threaten him with a popular uprising, a tactic he employed again in 1800 to force Roume to accede to the takeover of Santo Domingo.

By his own admission, Roume was no more than a “puppet” after the April 1800 chicken-coop incident in Haut-du-Cap, but his very presence implied that Louverture was a subordinate figure who needed France’s representative to countersign his decrees. Louverture treated him ever more harshly, eventually imprisoning him and his family in the town of Dondon. No longer pretending that the agent—that is, France—was the source of his authority, Louverture began to legislate under his own name. From that point forward, he was effectively an independent ruler.16

The philosophical justification for a ruler’s right to govern and the limitations of that power were two central questions of the Enlightenment. The Bourbon kings had once claimed that their unlimited authority stemmed from their exalted birth, and ultimately from God. To this, Jean-Jacques Rousseau had retorted that only the popular will could legitimize lawmaking. In the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the

Citizen, the French National Assembly had also enshrined certain inalienable rights that no legislating body could take away. But Louverture, like Napoléon in France and Simón Bolívar in South America, did not trust the people’s ability to make informed choices. Though he paid lip service to the republican principles of liberty and equality, he effectively instituted one-man rule. Enlightened dictatorship was his model, not the Enlightenment. Unlike John Locke, he did not advocate a representative government based on a social contract with the people. Instead, he styled himself after Plato’s philosopher king.

Following the invasion of Santo Domingo, Louverture felt strong enough to let French authorities know where their relationship with Saint-Domingue now stood. In February 1801, he informed them that he had deposed the agent Roume, a fact that he had kept secret until then. When sidelining previous officials, he had taken pains to accuse them of various wrongs, to print reports, and to dispatch envoys to Paris to justify his conduct. This time, he merely sent a batch of letters in which he accused the minister of the navy of “not doing him justice enough.” His tone verged on impertinence. Roume spent much of 1801 in captivity, and his health became so precarious that Louverture sent him to the United States, so that he would not die on his hands. France had no representative in Saint-Domingue thereafter, even in a purely symbolic role.17

In another letter sent in February 1801 and addressed to Napoléon, Louverture announced that he had just absorbed Santo Domingo in direct violation of his orders. Black troops had shown during the invasion that “they are capable of the greatest things,” he boasted. “I hope that, better disciplined, they will be able in the future to hold their own against European troops.” The subtext was clear: I may have disobeyed you, but if you ever try to overthrow me I will stand my ground.18

Louverture also explained in his letters that he intended to draft a constitution for Saint-Domingue. He was probably responding to the new constitution of the Consulate, a clause of which had proven controversial in Saint-Domingue: under the Directory, overseas territories had been treated as standard French provinces where French law applied by default, which guaranteed former slaves the same rights as all Frenchmen. Napoléon’s new constitution, by contrast, held that French colonies would be governed by distinct—but as yet unspecified—laws. Louverture and others in Saint-Domingue feared that Napoléon wanted to make possible the future restoration of slavery in some of the French colonies. These fears, it turned out, were well-founded. By preemptively enshrining emancipation in a constitution of his own, Louverture hoped to ensure that slavery could not so easily be restored in Saint-Domingue.

Under Louverture’s watchful eye, two deputies were elected in each of the five provinces of the colony: his native North; his adopted West; the South, which he had conquered from Rigaud; and two new provinces carved out of Santo Domingo. To play down the radical nature of the gambit, Louverture only picked white and mixed-race deputies, and he was careful not to describe the resulting constitutional assembly, which gathered in Port-Républicain in April 1801, as a fully sovereign body. He also avoided taking a public role in the deliberations. But there was no mistaking who was in charge: Louverture presided over the opening ceremony and ordered the deputies “not to divulge any of the legislative measures you plan to adopt before your work has been approved [by me] in its totality.” When Louverture left the city in May 1801, the constitutional deputies obediently followed their master from Port-Républicain to Cap.19

Louverture finalized the text of the constitution in June 1801, sent it off to the printer before France or the people of Saint-Domingue could weigh in, and then formally presented it to the population of Cap. That day, July 7, 1801, when he officially became governor of the island where he had once been a slave, was the most celebratory of his life. If we are to believe a nineteenth-century Haitian depiction of the ceremony, God Himself—depicted as an old white man—watched over the proceedings. Parades, adulatory speeches, a grand Mass, and a banquet for six hundred guests: the festivities matched those that had accompanied the arrival of a new French governor before the Revolution, a time when Louverture had observed the proceedings from afar as a slave. He was overwhelmed with a sense of pride and vindication. The official account of the ceremony noted in a flurry of capital letters that he had been “the Conqueror of his Country” before becoming its “Legislator,” and that his mind was now filled with the “memories of what he was and what he had become through the sole strength of his character.”20

Louverture’s conflicted approach to forced labor was a central theme of his constitution. It forcefully stated that slavery was forever abolished—a principle first introduced by a French commissioner in 1793, then approved by a French assembly in 1794, but one that Louverture had never personally proclaimed. “My fellow citizens,” he declared to the assembled masses, “whatever your age, class, or color, you are free, and the constitution handed over to me today is meant to safeguard this liberty forever.” But other articles of the constitution buried deeper in the text condoned his more reactionary policies, including the cultivator system and the importation of laborers from Africa. “Cultivators,” he admonished them for the hundredth time when presenting his constitution, “avoid sloth, the mother of all vices!”

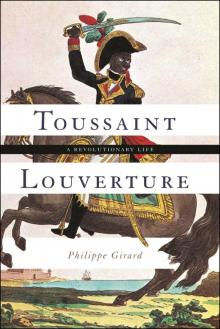

The July 1801 constitutional ceremony as reimagined in a nineteenth-century Haitian engraving. [François Grenier?], Le 1er Juillet 1801, Toussaint-L’Ouverture . . . (c. 1821), courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Though it referenced democratic principles like the separation of powers, the constitution turned Saint-Domingue into a de facto military dictatorship, foreshadowing the political culture of postindependence Haiti. Gone was the intendant who had shared power with the governor in prerevolutionary times; gone, too, were the gaggles of commissioners and agents whom France had sent during the Revolution. Gone were the warlords who had controlled various parts of Saint-Domingue during Louverture’s rise to power. There was now only one man in charge, who bore the title of governor general for life and oversaw both civilian and military affairs. “The Governor seals and promulgates laws; he appoints all civilian and military officials. He is commander in chief of the armed forces. . . . He sees to the internal and external security of the colony,” Article 34 explained. The seven articles that followed gave him extensive powers over lawmaking, the judicial process, censorship, taxation, trade, and finances. In another break from prerevolutionary practices, the colonial church also fell under the governor’s purview.

Summoning a constitutional assembly was Louverture’s most daring step yet, more daring even than the humiliation of Roume. A constitution was the social contract of a sovereign body: as such, it was incompatible with the colonial bond. The sole local precedent, the 1790 constitution passed by the assembly of Saint-Marc, had been widely interpreted in its time as a first step by white colonists toward Saint-Domingue’s independence. Tellingly, several veterans of the assembly of Saint-Marc served in Louverture’s constitutional assembly.21

Louverture’s constitution might still have passed muster in France if he had limited himself to delineating a semi-free status for former slaves and concentrating power in the hands of an executive branch that answered directly to Paris. Instead, several clauses directly challenged French sovereignty. Although Article 1 insisted that Saint-Domingue was “a colony that belongs to the French empire,” the rest of the constitution allowed Louverture to implement laws (starting with the constitution itself) without France’s prior approval. It also gave him a lifetime appointment with the right to appoint his successor, despite the fact that all previous governors had been appointed by France. Not even Napoléon, who was then the most prominent of a triumvirate of consuls, had yet dared to claim so much power for himself.

Coming so soon after the imprisonment of Roume and the invasion of Santo Domingo, Louverture’s constitution was viewed as a declaration of independence by all those who read it. “There seems to be no doubt left that the black

Toussaint Louverture is mulling over projects of independence,” the French ambassador to the United States had said after visiting the colony in the spring of 1801. When he read the constitution two months later, he concluded that his assessment of the situation had been correct: Louverture was now “in open revolt against France.”22

But was he? Louverture discussed forming “a black independent government” in a conversation with a British envoy, but he had mastered the diplomatic art of telling his partners what they wanted to hear. Anglo-Americans hoped that he would break from France, so he let them believe that this was his intention. Meanwhile, he repeatedly emphasized his loyalty to France when writing to Paris, as was expected of a French colonial official. This, too, was a lie. Louverture most likely had other designs: to gain as much autonomy from France as possible without crossing the threshold into outright independence. The strategy made sense in the current political environment. The British and the Americans became increasingly difficult diplomatic partners in 1801, so he had no reason to throw himself at their mercy. France retained its popularity with the black population as the homeland of emancipation, so he did not wish to give credence to the accusations of his enemies that he intended to forsake France and restore slavery.23

Finally and most importantly, Louverture had a very personal tie to France: his sons Placide and Isaac. By sending them to France to study, he had hoped to provide them with the kind of educational opportunities he had been denied as a child. He came to regret his decision as the years passed and his relationship with France soured. His sons became hostages guaranteeing his good behavior. “As long as you second the views of the government in Saint-Domingue, we will be pleased to fulfill your wishes regarding your children,” warned an official of the ministry of the navy. If not . . .24

Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture