- Home

- Philippe Girard

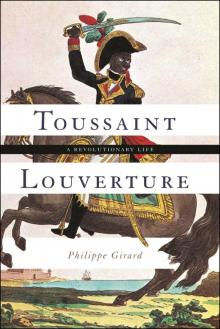

Toussaint Louverture Page 5

Toussaint Louverture Read online

Page 5

This parallel hierarchy of underground religious societies had been operating under the nose of French authorities for years. The leader of the underground movement was a man known as Makandal, a Kreyòl term meaning “sorcerer” or “talisman.” Makandal had been a slave himself, toiling on a sugar plantation before losing his hand in a mill accident and running away. For ten years he had been able to hide from authorities: other slaves were deathly afraid of his abilities and dared not denounce him. It was only in 1758 that the French finally managed to capture Makandal, interrogate him, and try him in court.

Makandal was publicly tortured so as to force him to reveal the name of his accomplices. Then, according to his sentence, he had to “make amends, wearing only a shirt . . . in front of the parish church . . . while bearing signs on his front and back inscribed seducer, blasphemer, poisoner.” He would then be burned alive.12

Makandal’s final moments proved memorable. As the flames closed in on him, he managed to break his ties in a desperate, superhuman effort. The slaves in the audience, who thought that Makandal had the ability to transform himself into a mosquito at will, gasped “Makandal is free!” A riot seemed near. Authorities cleared the plaza to restore order, forced Makandal back onto the fire, and executed him as planned, but many slaves did not witness the moment of his death and remained convinced that he had flown away unscathed. Proof of Makandal’s handiwork came later that year, when the intendant (the official who had overseen the investigation) suddenly died, as did his successor. For decades thereafter, slaves whispered that Makandal would return one day to free them—and in at least one sense, he did: mosquito-borne tropical diseases were a main cause of France’s defeat during the Haitian Revolution.13

The poison scare and the hunt for Makandal must have made a deep impression on the young Louverture. Makandal’s original plantation in Limbé was just a few miles from Haut-du-Cap; his roaming grounds as a runaway likely included the hills of Morne du Cap above the plantation. It is even possible that Louverture, who was fifteen years old at the time, attended Makandal’s January 1758 execution, which took place just outside the Catholic church that he normally attended. The following months and years were also hard to ignore. Chastened by the episode, French authorities created new regulations limiting slaves’ ability to travel without a pass; to bear arms, even to protect livestock; to buy medicine for their masters; or to earn cash on the side. All of these things had been tolerated before.

French officials were not the only ones to be afraid of Makandal’s second coming: Louverture developed such a lasting horror of poison during the Makandal conspiracy that four decades later, as governor of Saint-Domingue, he had all his meals monitored for fear that a rival might murder him. He was not one for magic tricks and Vodou rituals, even in the name of freedom.

Short of outright revolt, the most effective form of resistance was to become a maroon, a term derived from the Spanish word for a wild animal (cimarrón) that was used to describe slave runaways. The Black Code punished maroonage harshly (branding for a first offense, hamstringing for a second, and death for a third), but such punishments were later lessened to hard labor or prison time. Some slaves, accustomed to the hardships of plantation life, viewed the latter “as a time of rest rather than punishment.” Cases of maroonage were accordingly numerous, so much so that a rural police force, composed primarily of free people of color, was set up in 1721 specifically to catch runaways. Even then, there were enough maroons around Cap for a section of the local newspaper to deal exclusively with runaway notices.14

The Bréda plantation in Haut-du-Cap was particularly prone to maroonage. “I don’t know what to do with four young creole slaves from this plantation,” complained an attorney. “When they are not enchained, they run away.” A grove of banana trees was a favorite escape route. The hills of Morne du Cap, which abutted the back of the plantation, also made for an easy hideaway. One Bréda runaway, who bore the unusual name of Sans Souci (literally, “no worries”), may have been the same Sans Souci who later led a large rebel group during the Revolution, in which case he and Louverture would have been old acquaintances.15

The freedom trail could reach quite far. One Bréda runaway made it all the way to Port-au-Prince; others joined autonomous maroon communities in Saint-Domingue’s interior, or, more frequently, crossed the border into Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) to claim asylum. The French negotiated an extradition treaty with Spain in 1776–1777 to curb the practice, but Santo Domingo’s reputation as a safe haven was sufficiently well established that many rebels, Louverture included, sought refuge there when the Haitian Revolution broke out. Even more troublesome were the runaways who stayed close to their plantation of origin and, like Makandal, stirred trouble among the enslaved workforce.16

Slave runaways foreshadowed the Haitian Revolution in many ways, but they did not yet have a political agenda. They hailed from a world in which slavery was an established part of life on both sides of the Atlantic, so imagining that free labor could be the norm would have required a complete change of paradigm. In Haut-du-Cap, slaves did not flee their plantations to bring slavery to its knees—a ludicrous and even unthinkable idea at the time—but to protest excessive punishments or the lack of food. They then returned to work after they had obtained what they sought. The practice became systematic under the tenure of the attorney Gilly in 1764–1772, when slaves became used to “running away together as soon as [their masters tried] to punish them,” in order to put pressure on their overseers and obtain better work conditions. They had discovered the ultimate French institution: the strike.17

After Gilly’s death in 1772, the attorney’s position was briefly held by his protégé François Bayon de Libertat. But Bayon made the mistake of overspending on new buildings without seeking prior permission from the absentee owner, who sacked him in April 1773, and another attorney named Delribal took over. Delribal was convinced that his predecessors had been far too lax, and that it was time to restore discipline. Events gave him an opportunity to showcase his determination. A cattle epidemic had just begun to sweep through the plantations of the plain of Cap, killing dozens of mules, oxen, and cows on the Haut-du-Cap plantation. Veterinarians attributed the deaths to some previously unknown disease, but Delribal, drawing from the Makandal precedent, blamed poison instead. He arrested the slave in charge of the mill’s mules, Louis, another slave named Jean-Baptiste, and the sugar refiner Ouanou. He then tortured them to force them to confess that foul play was involved.

A distraught Louis cut his own throat with a broken bottle, but his suicide attempt and the lack of evidence did not discourage Delribal. He built a private prison on the Haut-du-Cap estate, began to threaten more arrests, and wrote to the absentee owner to let him kill one slave as an example. This must have been a terrifying period for the slaves of Haut-du-Cap. Years later, during the Revolution, one of the rebels’ first demands was the abolition of private prisons like the one set up by Delribal. Louverture’s name, strangely, is not mentioned in surviving documents, but he must have followed the events closely because cattle and horses were his area of expertise.18

Under the Black Code, victims of egregious planter misconduct were supposed to appeal to royal authorities, who would then prosecute the planter on their behalf. But recent attempts by neighboring slaves to do just that had shown that it was almost impossible to overcome the pro-planter bias of the courts (for one thing, slaves could not legally take the witness stand). Slaves typically lost their cases and were sent back to their home plantations to endure whatever vengeance their owners saw fit to inflict. So the Bréda slaves tried a different technique: in September 1773, twenty-five of them absconded, and then appealed to relatives of the Brédas who lived in the area.19

Their timing was good. The flight of so many slaves was a major financial blow. Production plummeted, and Delribal, for all his tough talk, had to spare the runaways when they returned as a group in October 1773. Labor frictions were still

far from over: one month later, when Delribal ordered a slave whipped for stealing sugar, thirty-six more slaves ran away.

Delribal’s tumultuous tenure ended a month after that, when he received news from France that Pantaléon de Bréda Jr. had fired him after just a few months in office—not for brutalizing the slaves, but for his poor financial performance (Pantaléon Jr. had just purchased an expensive residence in Paris and urgently needed cash). François Bayon de Libertat, who had kept the absentee owner informed of his rival’s misdeeds throughout the crisis, got his old job back; it is even possible that Bayon had egged on the slaves behind the scenes. Bayon then simply waited until the cattle epidemic died out in 1775.20

Historians usually describe Bayon as a gentle master, because Louverture wrote that “his workers loved him like a Father, and in return he treated them with untold kindness.” Bayon did treat elite slaves well, which may explain Louverture’s fond recollections, but his behavior toward field hands was little better than Delribal’s. Like his predecessor, he had to contend with episodic strikes from a slave workforce that was anything but submissive (one Bréda slave was even caught with a loaded gun). Like his predecessor, he employed fear to quell unrest. He shackled troublesome slaves with an iron boot, a kind of metallic brace that made it impossible to bend one’s legs, and he kept troublemakers locked up in a small cell for months like some badly behaving dog. Louis and Ouanou, the two slaves abused by Delribal in 1773, spent part of 1775 there. This must have been a trying experience in a tropical climate, and Louis passed away after a four-month stint in the cell. Bayon expressed some regret for his death, but only because Louis had “talent” as a sugar refiner, and his death was a financial setback. He mentioned the death of older slaves with barely disguised glee: too weak to do much work, “they had become a burden.” Such was the “kindness” of Bayon.21

How much did Louverture involve himself in the various forms of resistance employed by the slaves of prerevolutionary northern Saint-Domingue, both big and small—specifically the Makandal conspiracy in the 1750s and the strike against Delribal in the 1770s? There is no firm evidence tying him to either incident, probably because the first was too closely associated with Vodou, and the second entailed too much physical risk. Instead, he kept his distance and watched on like some apprentice revolutionary learning his trade. He was by nature a cautious man—especially now that he had a family to care for.

FIVE

FAMILY MAN

1761–1785

A SOMBER CEREMONY took place in the swamp of La Fossette, a short distance from the Bréda plantation in Haut-du-Cap, on November 17, 1785: the funeral of a young man named Toussaint, who had just died at the age of twenty-four. His brother Gabriel Toussaint followed the procession. Funerals of prominent slaves were important affairs, possibly because Haitian folklore held that the dead haunted their relatives as zombies if they were not properly buried. “A considerable crowd of African slaves accompany their [deceased] comrades to the cemetery,” described a chronicler. “Women sing and clap their hands, followed by the dead, and then the negroes. A negro marches by the coffin and regularly hits a drum in a gloomy manner.”1

The white priest likely grumbled about having to walk all the way from his church in Cap to the new cemetery of La Fossette in the outskirts of town (the previous cemetery had been unhealthily but conveniently located downtown). But there was no time to lose: in keeping with Caribbean practices, where the warm weather did not allow for extended mourning periods, the young Toussaint was lowered into his grave just hours after he died. Priests usually kept religious rituals to a minimum because authorities paid them no extra fee for black funerals, but perhaps the priest made an exception on that day because the father of the deceased was very well known to him. He was one of his most devout parishioners and a muleteer on the nearby Bréda plantation. His name was Toussaint Louverture.

The burial certificate, tucked away in the French colonial archives in Aix-en-Provence, came as a surprise when it first surfaced in 2011, because neither Toussaint Jr. nor his brother Gabriel Toussaint were known to scholars. Also surprising was the identity of their mother, a black woman named Cécile who was identified as Louverture’s wife. For two centuries, historians had only known of another wife, named Suzanne, and two other sons who were born at a much later date. This first family, suddenly rescued from history’s void, cast new light on an overlooked but central facet of Louverture’s personality.2

Saint-Domingue was a terrible place to raise a family. The imbalanced sex ratio made it difficult for men to find a spouse, and disease, overwork, natural disasters, and war meant that deaths far exceeded births. An owner’s death could break apart one’s family at any time; a master could rape one’s wife and daughters with impunity. In this unfavorable context, most male slaves died alone and childless. And yet Louverture managed to marry not once, but twice. He had biological children, illegitimate children, a stepson, an adopted daughter, a stepmother, two biological parents, and two surrogate parents, along with a bewildering collection of nephews, siblings, goddaughters, and in-laws. This sprawling family network allowed him to cope with slavery; much later, it would also form the backbone of his revolutionary regime.

Marriage—a difficult proposition in any slave system—was a rarity among the slaves of Saint-Domingue. The first obstacle was simple arithmetic. African traders preferred to sell their female slaves in Africa or the Middle East, where they were sought after as domestics and concubines, so the majority of the slaves purchased by French traders were males (179 men for every 100 women), who were better suited for the backbreaking toil of the sugar plantations anyway. The ratio was slightly less lopsided on old plantations, where births evened out the population over time; but the Haut-du-Cap plantation’s unusually high rate of deaths and slave purchases meant that it still had 152 men for every 100 women as late as 1785. In much of Africa, it was a sign of social success for a man to marry several brides. In Saint-Domingue, polyandry would have made more sense.3

The problem was compounded by some masters’ blanket opposition to marriage (which had a way of complicating the sale of family units), as well as by reluctance on the part of male slaves to bind themselves to a “form of servitude that is even more onerous than the one they were born into” (or so judged a misogynistic Jesuit author). By choice or by necessity, many slaves, especially field slaves from Africa, entered into temporary informal unions instead of church marriages—that is, if they could find a partner at all.4

Louverture distinguished himself from his peers as he embraced the European model of a formal marriage sanctioned by the Catholic Church. Toussaint Jr. was listed as legitimate in his 1785 death certificate, so Louverture must have married Cécile in or before 1761, when he was just eighteen. We know very little of his first wife except that she had a brother, Tony, who was “given to drinking and lazy.” Like Louverture, he was a coachman on the Bréda plantation.5

Motherhood was not an attractive proposition for slave women like Cécile. Giving birth meant bringing yet another slave into the world. The Black Code specified that family units had to be kept together, but experience taught otherwise. In any event, masters made few efforts to encourage natural reproduction; concluding that it was cheaper to import a ready-made worker from Africa than to feed an infant slave to adulthood, they usually gave no time off to pregnant or nursing mothers. In this context, why add child-care duties to one’s long hours in the fields for the sole purpose of enriching one’s master? Infanticide and abortion were disturbingly common, and the fertility rate of Dominguan slaves was among the lowest in the world (a quarter of the women never even became pregnant).

Only as the century progressed and the price of imported slaves rose did some masters begin to pursue pro-natal policies to save money. On their plantations, the Brédas began to exempt women from field labor after they gave birth to five children as an incentive to procreate. Results were mixed. “Your negresses in Plaine-du-Nord have not had chi

ldren for years,” reported a Bréda attorney, “but in Haut-du-Cap there are always a few.” Two slave mothers in Haut-du-Cap—Hélène and Marguerite—had five children or more by 1778. Another twelve babies were born on the plantation from 1780 to 1785, most of them to domestics and specialized slaves like Louverture, leading the accountant to grumble that “the master house looks like a nursery.”6

It was in this uncertain environment that the young couple then known as Toussaint and Cécile Bréda began a family of their own. They had three children together, two boys and a girl. The oldest, named Toussaint like his proud father, was born in 1761. Later came Gabriel Toussaint and a girl named Marie-Marthe (aka Martine). If one includes his later marriage and extramarital dalliances, Louverture fathered or adopted sixteen children during his life, an indication of his unusual social prominence. Tragically, he outlived eleven of them, starting with his first-born son, Toussaint Jr.7

Enslavement shaped every aspect of marriage and family life. Though masters could not have intercourse with their female slaves under the Black Code, the clause was routinely evaded in a world where white women were few and slave women vulnerable. “Nothing more common than the debauchery that exists between whites and the women of color, both mulattresses and negresses,” noted a visitor.8

Toussaint Louverture’s family tree. Figure by the author.

Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture