- Home

- Philippe Girard

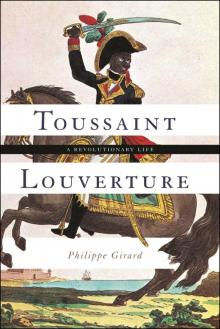

Toussaint Louverture Page 8

Toussaint Louverture Read online

Page 8

Louverture never mentioned this deal thereafter, to avoid damaging his revolutionary credentials, but it was a turning point in his life, more meaningful in some ways than his recent manumission. He had become a freedman, and then a slave driver. He was one of them. A general law of emancipation was unthinkable at the time, so making money by any means necessary was the only way he could free his relatives. Money was liberty.

View of Cap from the southeast. The plantation of Haut-du-Cap was located at the foothills of the Morne du Cap, to the left of this picture. From Taylor, Vue générale du Cap-Haïtien (nineteenth century). Personal collection of the author.

Unfortunately, Louverture had not picked the best time to go into business. Racism toward free people of color was becoming increasingly institutionalized in Saint-Domingue and the war made for a difficult economic context. The experience was a sobering one. Within two years, Louverture lost his money, his lease, his wife, and, for all practical purposes, his freedom.

Saint-Domingue’s free people of color were not rebels: they were strivers. Despite their full or partial African ancestry, they looked up to white planters—and ultimately to France—for inspiration. They thought more highly of standard French than of Caribbean Kreyòl; they publicly rejected the Afro-Caribbean religion of Vodou in favor of Roman Catholicism. They also wanted to get rich the same way every white Frenchman wanted to get rich: by buying and exploiting slaves.2

Their strategy paid off early in Louverture’s life, when race was defined as much by one’s financial success as by the color of one’s skin: some wealthy mixed-race planters managed to be listed as white in legal documents. But as the years passed there were increasing efforts to treat any amount of African blood as a stain that could not so easily be erased. By the 1760s, so-called scientific racism, a biological definition of race that was less flexible than the socioeconomic definition that had preceded it, was becoming the norm.

There was nothing preordained about the rise of racism in Saint-Domingue. The word “race” did not even exist in the French language until the fifteenth century, and even then it often referred to one’s class background rather than the color of one’s skin. Racism began as a man-made historical phenomenon in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War, when French authorities purposely fostered tensions between free whites and free people of color for fear that they might unite in a common bid for independence. White planters quickly embraced racism for their own practical reasons: they hoped that slaves would be more docile if they were “intimately convinced of the white man’s infallibility.” Because people of color outnumbered whites twenty to one, a white colonial author argued, “safety demands that we treat the black race with such contempt that anyone who descends from it, until the sixth generation, must be indelibly stained.” Down the social ladder, “little whites” welcomed the notion that the color of their skin somehow made them superior to mixed-race planters who outranked them in every other aspect. In time, racial theorists developed the pseudoscientific theories white people needed to rationalize their self-interest.3

Louverture did not have to look far for evidence of racism’s growing hold. The most famous racial controversy in 1770s Saint-Domingue involved none other than his old boss François Bayon de Libertat and a neighboring planter named Pierre Chapuizet. Chapuizet’s great-great-great-grandmother was apparently an African slave, but one’s racial background had been less important in the early 1700s, so many legal documents had failed to mention his mixed ancestry. Things changed in 1778, when Chapuizet applied for an officer commission in a white militia unit. Local white planters, spurred on by Bayon, rejected his application because “there are certain stains that a court decision cannot erase perfectly . . . or whiten sufficiently.” Suits and countersuits flew back and forth until July 1779, when the appeals court in Cap affirmed that Chapuizet was legally white, sentencing Bayon to a fine of 150 livres and a public apology for suggesting otherwise.4

Free people of color (including, apparently, Louverture) loudly celebrated the court’s decision in Chapuizet’s favor, but their joy was misplaced. The court did not outlaw racial prejudice when it declared that Chapuizet was legally white: it merely left open a path by which a handful of light-skinned individuals like Chapuizet could repudiate their African ancestry and pass as white. The principle remained that African ancestry was to be considered shameful and that people of color could only be declared equal by special dispensation (such was also the norm for the Jews of Saint-Domingue, one of whom spent the same summer of 1779 petitioning for individual citizenship rights). Only the French and Haitian revolutions would make all men free and French regardless of their race or creed.5

Such a radical concept was still unthinkable in the Caribbean of the 1770s. Racism so permeated society that people of color, instead of rejecting its underlying principles, instead made it their own. Mulattoes and quadroons resented being excluded by whites, but they kept their distance with black freedmen like Louverture, who in turn treated their African-born brethren as less civilized. The chain of contempt ended with the newly imported slaves, the bossales, a term derived from the Spanish bozales (muzzled, or shackled), but that was often rendered in French as peau sale (dirty skin).

Louverture’s own relationship to race was a complex one. He was sensitive to any racial slight, but he also longed to be accepted by white planters, who were held up to him as a model for the first half-century of his life. He was envious and critical of mixed-race mulattoes, and he favored his mixed-race stepson over his biological black son. He was a product of his age.

The growth of racial prejudices had important consequences for Louverture and his fellow black freedmen, who were supposed to be equal to free whites under the 1685 Black Code, but were progressively subjected to discriminatory colonial laws. After 1767, free people of color could no longer claim noble status or hold public office, and in 1774 white men married to women of color were placed under similar restrictions. Authorities began to require that a person’s race be listed on legal documents, and in 1773 they denied people of color the right to use a French last name, in a move to emphasize their African ancestry. By 1779, free people of color could not even wear clothes as luxurious as those of whites, and they could not stay out dancing after 9 p.m., as if they were slaves on the lam. For the mixed-race offspring of white planters, who had always thought of themselves as French, the rejection took on Oedipal tones. “O, my fathers!” one of them lamented. “Because you had us with Africans, you think we cannot feel and think like you?”6

Some of these laws hit close to home for Louverture. When his daughter Marie-Marthe freed her mixed-race child, by law she had to pick an African name for him, so that he could not be mistaken for a “real” Frenchman. Initially named Toussaint after his grandfather, the boy had to change his legal name to Lindor. One generation earlier, Louverture’s parents had been stripped of their African identity and given new Christian names; French authorities now insisted that the next generation could never escape its African roots. Neither African nor French, Caribbean Creoles like Louverture were cultural nomads.7

Every interaction with whites became fraught with danger. In 1780, the coachman of a Bréda heir who was returning home from work was shot on sight by rural policemen, who were out “hunting maroon negroes” and suspected him of being a runaway. The penalty for this wrongful death was a simple fine.8

The most prominent free people of color did not stand hapless. They ignored the laws that did not benefit them and were not afraid to sue to implement those that did, sometimes successfully (suing one’s neighbor was a favored pastime in Saint-Domingue). The Bréda family alone lost no fewer than five civil lawsuits against mixed-race neighbors around 1780: Bayon’s attorney, already hard at work on the Chapuizet case, must have been a busy man and a bad lawyer. But Louverture did not have the legal resources or social standing to fight back in court and simply learned to respond to white harassment with meek submissiveness.9

In t

his already tense racial context, news that the thirteen British colonies in North America had formally declared their independence hit Saint-Domingue in the summer of 1776. The American rebels found it “self-evident, that all men are created equal”: for free people of color in the Caribbean, these stirring words seemed to foretell a new era in which one’s legal status would be based on universal ideals rather than crass calculations about profit and loss. But the US Declaration of Independence had been written by a slave owner, so maybe this revolution would not lead to meaningful change.10

The reaction of the white colonists hovered between dread and jubilation. A French war with Britain, which seemed likely, would disrupt trade links and cause food shortages in Saint-Domingue, a worrisome prospect, since a drought had already pushed the Bréda slaves to the edge of starvation. “It would be a shame for us if we had a war,” worried Bayon, who wondered how he was going to export molasses to New England past British warships. But there was something enticing about white planters setting up a government of their own while keeping intact the plantation system that had made them rich. After all, were Dominguan Creoles not Americans as well? “Everyone here believes very strongly that . . . this country [the United States] will be independent,” Bayon wrote excitedly after receiving news of the rebel victory at Saratoga, evidently having changed his mind about the risks involved.11

Paris balanced its options carefully. On the one hand, if the North American rebels succeeded, it would set a bad precedent for France’s own colonies. On the other hand, anything that was bad for Britain was good for France. France also feared that a reconciliation between the United States and Britain would be sealed by a joint attack on Saint-Domingue. After thinking the matter over, King Louis XVI decided to support the rebels, declaring war on Britain in February 1778. Spain followed suit a year later.

The war’s impact was felt acutely in Cap. A British squadron blockaded the port in the fall of 1778, making it virtually impossible to export goods and forcing Bayon to stockpile sugar. Fearing an invasion, royal authorities demanded that the slaves of local planters help overhaul the colony’s fortifications. As the plantation located closest to Cap, Haut-du-Cap was hit particularly hard by such requisitions.

Who should defend the colony was another contentious issue. France had long wished to supplement its regular regiments from Europe with local recruits who were less susceptible to tropical diseases, but white colonists were averse to any type of military service. It was only after overcoming an armed white uprising that colonial authorities had been able to create a militia in the mid-1760s. The issue rose again during the US War of Independence, when, in 1779, Admiral Charles d’Estaing headed to Cap with a large fleet. He made urgent requests for troops to replace the 1,500 men he had lost to disease since reaching the Caribbean, and the governor of Saint-Domingue set out to create volunteer units of colonists. Both whites and free people of color could enlist, but they would be assigned to different units.12

The public response was mixed. Only 156 white Dominguans offered to join d’Estaing’s force; most other whites viewed military service as a dishonorable and unrewarding profession good only for “little white” ruffians. By contrast, no fewer than 941 free people of color volunteered. They saw military service as a way to prove themselves as French patriots at a time when they were being relegated to second-class status by law. The Saint-Domingue volunteers were incorporated into two units: whites formed a unit of elite assault troops, the Grenadiers volontaires, while people of color formed a much larger unit of light infantrymen, the Chasseurs volontaires.13

Many of the Chasseurs were destined to become famous in the Haitian Revolution. Jean-Baptiste Chavanne, who would lead an important uprising in 1790, was among them. So were André Rigaud, who would become a general and Louverture’s main rival in the 1790s, and Jean-Baptiste Belley, who later served as deputy in the French parliament. According to Haitian traditions, the expeditionary force also included Henry Christophe, who went on to serve as general under Louverture. Louverture’s son-in-law Philippe Jasmin Désir likely joined as well, as did his future son-in-law Janvier Dessalines.14

Louverture, meanwhile, stayed put. He had a more lucrative plan in mind.

It was in August 1779, just as the fleet was preparing to set sail for North America, that Louverture signed the lease to rent Désir’s coffee estate and thirteen of his slaves. The document did not provide the rationale for the transaction, but the historical context strongly suggests that Désir had hired Louverture to serve as a caretaker during his absence.15

This was the riskiest and most ambitious business venture that Louverture had ever attempted. In addition to 1,000 colonial livres of yearly rent, he pledged to reimburse Désir for the cost of the slaves, valued at 16,500 colonial livres in all, who might die under his care or flee. The deal clearly stretched his resources. To pay the first year’s rent, Louverture had to sell part of a small plot of land he had bought just six months earlier. He also put up the rest of his assets as collateral.16

To manage the estate, Louverture had to leave Haut-du-Cap, where he had spent all his life, and move ten miles south to the hamlet of Petit Cormier, which stood on the left bank of the Grande-Rivière (Great River) as one traveled upstream from the town of the same name. Lying south of the sugar-making plain of Cap, the county of Grande-Rivière was a hilly area dotted with 329 coffee estates. The region was known for producing centenarians, including the famed black veteran Vincent Olivier, whom Louverture had probably met in Cap (he died in 1780 at the alleged age of 119).17

Coffee was a new but booming crop in Saint-Domingue, on a path to supersede sugar as the colony’s signature export. The low up-front costs involved made it particularly attractive to an undercapitalized freedman like Louverture, but it required a cultivation process that someone who had spent his life on a sugar estate would have found arcane. After the coffee cherry was harvested from the bushy trees, it had to be cleaned, dried, milled, husked, and sorted. The profitability of Louverture’s venture would depend on getting every step right.

Louverture knew how to manage workers, but now there was one key difference: he was no longer an elite slave supervising fellow slaves, but a freedman exploiting slaves he had rented from their owner. The fact that all thirteen of Désir’s slaves—a man, his four sisters, and their eight children—belonged to the same family must have made for a strange work environment as well. Picking coffee was not as physically demanding as harvesting sugarcane, but the death rate from lung afflictions could be high on coffee plantations on account of the cooler air of the hill country, a frightening prospect, considering that Louverture was financially responsible for the life of each of the slaves.

Among the eight young slaves of the family, the costliest was Jean-Jacques, valued at 1,500 livres. It came to light in 2012 that he was none other than the person known to us as Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who later became the first leader of independent Haiti. Dessalines is Louverture’s equal in the eyes of many Haitians, so their prerevolutionary ties came as a jolt, as if it had suddenly been revealed that Thomas Jefferson had once been George Washington’s indentured servant. The complex dynamics of Louverture and Dessalines’s relationship—at once close, unequal, and contentious—likely originated during the period when the young Jean-Jacques toiled as a slave under the freedman Toussaint Bréda on the coffee estate of Petit Cormier.18

When Admiral d’Estaing’s fleet left Cap in August 1779, its mission was to seize the British-held town of Savannah, Georgia. But the experience of war proved less exhilarating than the volunteers of the Chasseurs unit had hoped. Though many of them were socially prominent in Saint-Domingue, they were assigned menial tasks, such as digging trenches. Only during a final French assault on Savannah were they able to prove their mettle: the British counterattacked, and the Chasseurs successfully defended the French camp. The siege itself was inconclusive, however, and the French expeditionary force withdrew after a few months.19

&nbs

p; Leaving the French Army proved to be more difficult than joining it. The Chasseurs considered themselves civilians, and they expected to return home after the siege, but the French high command was reluctant to let go of trained men in the midst of a war. It would be three years before some of the men would again see Saint-Domingue. When they did, they received no hero’s welcome: the Chasseurs had hoped to be accepted as French citizens through military service, but they returned to the same segregated colony they had left. Within a decade, their disappointment would morph into a movement for racial equality.

Although it was a military failure, the Savannah expedition served an important long-term political purpose. Free people of color, who already served in the rural police (maréchaussée) and the militia (milice) in Saint-Domingue, learned in Savannah that they could be a fighting force equal to any white army. The lesson was not lost on the various Savannah veterans who later participated in the Haitian Revolution.

The war had not been a boon to Saint-Domingue’s economy in the Chasseurs’ absence. As French and Spanish troops flooded the colony, demand and prices for foodstuffs rose precipitously, as did the cost of every item needed to run a plantation. Meanwhile, few tropical crops were exported, because of frequent British naval blockades, so sugar and coffee piled high in the warehouses of Cap while their prices plummeted. A hurricane hit in November 1780, followed by torrential rains, leaving a trail of devastation, particularly in the Grande-Rivière area. By the following spring, drought was a concern. Then the flooding returned. “The colony is devastated: we need peace,” wrote Bayon in March 1781.20

Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture